When it comes to ancient healing, few substances carried as much weight — both practical and symbolic — as frankincense and myrrh. Long before tablets and tinctures came in amber glass bottles or with barcodes, these resinous treasures flowed through the hands of priests, physicians, and traders in the heart of Mesopotamia and along the golden banks of the Nile. They weren’t just part of ancient life — they shaped it.

When it comes to ancient healing, few substances carried as much weight — both practical and symbolic — as frankincense and myrrh. Long before tablets and tinctures came in amber glass bottles or with barcodes, these resinous treasures flowed through the hands of priests, physicians, and traders in the heart of Mesopotamia and along the golden banks of the Nile. They weren’t just part of ancient life — they shaped it.

Let’s rewind several thousand years. In Sumer and early Babylon — those early powerhouses of Mesopotamian culture — frankincense wasn’t simply burned for scent. It marked boundaries between the everyday and the sacred. Dusty temples, lit by flickering oil lamps, were thick with its smoke. This wasn’t ornamental — it was spiritual hygiene. The air was being cleared, quite literally. The smell alone changed the atmosphere. Sacred became safer. People stood taller.

But it wasn’t just temples and altars. Clay cuneiform tablets — which we’d mistakingly call “low-tech” — offer records of frankincense and myrrh being mixed into healing balms and poultices, often alongside honey or animal fats. Ancient healers had no illusions. They understood that something about the resins went deeper than surface healing.

“A physician without knowledge of divine essence cannot treat the soul or the body.” — ancient Mesopotamian scribal teaching

That understanding carried over — with variations — to the Egyptians. If you look past Hollywood’s gloss and dig into the Ebers Papyrus, a.k.a. one of the world’s oldest medical texts, you’ll find frankincense and myrrh scribbled repeatedly among remedies. Egyptians didn’t just embalm the dead with myrrh — they took small amounts internally, combined it with wine, or used it to treat infected wounds. Frankincense oil? Mixed with crushed moringa seeds and palm wine to freshen breath. Funny how some things never change.

According to archaeobotanical research, myrrh shows up in over 60 different traditional Egyptian recipes, including ointments for skin disorders and enemas aimed at clearing internal blockages.

Here’s one that might hit closer than expected: in both cultures, myrrh was frequently used to ease grief. Whether in incense at funerals or as a tea for the mourning, its grounding scent served a purpose — helping people process transitions no herb or philosophy could make easy. That tells you something about how these cultures saw healing — not just as a medicine for the meat of the body, but for the spirit stretching inside it.

You know what? Ancient Egyptians were one step ahead in pharmacology too. Their priests guarded medical knowledge like their gods — methodical, almost clinical in their experimentation. Wounds were cleaned with honey, then packed with myrrh paste to prevent rotting. Want to talk about antimicrobial medicine before microscopes? There it is, plain and unvarnished. You can almost smell the sharp sweetness in a desert breeze.

A subtle detail here: both resins were imported. They grew in distant lands — Oman, Somalia, across the Arabian Peninsula. That meant they had to be brought north on camel caravans or sea routes, making them expensive and symbolic of wealth and intention. When someone burned frankincense in a temple or rubbed myrrh into a wound, it wasn’t done casually. It meant something. Reverence wasn’t an option — it was built in.

The term “biblical medicine” is often thrown around today like a buzzword, slapped on soap packaging or essential oil blends. But zoom back to ancient Nineveh or Thebes, and it meant real knowledge passed on in chants, tattoos, bundles, and smoldering prayers — much of it unrecorded. Do we remember it all? Probably not. But the echoes still ring if you stop and pay attention.

And maybe that’s part of the strange beauty here. Neither Mesopotamian nor Egyptian healers saw a line between the practical and the sacred. To clear a space with incense was also to make it healthier. To wrap a wound in resin was also to invite something unseen into the healing.

They didn’t need textbooks to teach that kind of wisdom. They just listened — to the body, to the smoke, to the silence.

Medicinal applications in ancient Greece and Rome

You shift the scene westward, and suddenly we’re in the marble courtyards of ancient Greece, where medicine walked with logic on one side and mystery on the other. This wasn’t medicine as we know it — it was part philosophy, part observation, and part trust in nature’s hidden order. Frankincense and myrrh fit right in with the Hippocratic oath and Pythagorean numerology, not as exotic imports but as dependable allies in physical and emotional recovery.

Walk into an old Greek apotheke, and you’d find jars of powdered herbs, oils, and resins stacked beside mortar-stained counters. Galen, the Roman physician whose work influenced European medicine for over a millennium, frequently prescribed myrrh for what he called “putrid wounds” and used balsamic mixtures to address respiratory issues. He might’ve not known much about volatile compounds or antiseptics in modern terms, but he watched closely. Burned flesh that healed faster? Less swelling? That mattered — observation was the gold standard.

“The art of healing comes from nature, not from the physician. Therefore, the physician must start from nature, with an open mind.” — Paracelsus

Consider how myrrh was often mixed into mouthwashes and skin salves in Greece — not because it smelled nice (though that helped), but because it actually worked. According to modern studies like those published on the NCBI, myrrh demonstrates strong anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. The ancients knew it through outcomes, not graphs. Swollen gums shrank. Sores mended without festering.

Frankincense, on the other hand, was more often treated as a gentle purifier. For the Greeks and, later, the Romans, it supported digestion — a few drops in warm wine after a heavy meal was seen as harmonizing the belly and subtle energies alike. Physicians even used frankincense smoke to ward off what Hippocrates might have called “bad airs” — their term for environmental causes of disease. Kind of like cracking a window after burning garlic, only with way more intention.

Meanwhile, those practicing what we now vaguely term “biblical medicine” — early Christians, Jewish healers in Romanized Judea, and some fringe Hellenistic cults — kept using these resins not just materially but symbolically. Myrrh, bitter and earthy, was used to treat both internal pain and external wounds, suggesting a resonance between bodily and spiritual suffering. In Mark’s gospel, Christ is offered wine mixed with myrrh before crucifixion — a detail that’s more than scriptural poetry. It’s a form of pain relief. A bitter cup meant to ease the final stretch.

And this wasn’t rare. Roman physicians wrote of myrrh as a component in complex ointments like “theriacs,” which were elaborate blends used to fend off poisons or infections. Think of them like an ancient version of an immune-boosting tonic — turmeric and black pepper’s spiritual grandparents. Some formulas had up to 60 ingredients, but the heavy hitters often included myrrh for its stabilizing and preserving power.

The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote that myrrh “cures all afflictions of the mouth and heals every kind of wound.” Not casual praise, coming from a man who catalogued nearly everything from meteorites to medicinal mushrooms.

Let’s pull back for a second. In both Greece and Rome, medicine wasn’t just a job — it was a calling. Temples dedicated to Asclepius were not only houses of healing but places of ritual sleep, where dreams guided diagnosis and recovery plans. Frankincense burning during those rituals wasn’t an aesthetic touch. It was signal fire — cuing the nervous system to relax, breathing to slow. Kind of like what an herbalist today might achieve with a strong cup of lemon balm tea.

And yet, not everything was so peaceful. War wounds were common, and resins weren’t just symbolic — they were battlefield necessities. Roman legion medics, known as capsarii, often carried myrrh-based pastes to pack into gashes and bites. No one called it “antimicrobial,” but soldiers knew a treated wound was less likely to stink and more likely to heal.

There’s something else hiding in plain sight here: cost. Myrrh and frankincense were imported from the Arabian Peninsula, Ethiopia, and India, traveling across trade networks that mirrored and fueled empire expansion. That meant they had value beyond medicine — they were political, economic, even sacred currency. A shopkeeper might trade a bolt of fine wool for a tiny jar of resin. A traveling priest might carry a pouch not for prayer, but for protection against disease.

What’s easy to miss in all this history is how practical and flexible these ancient people were. They didn’t isolate “body” from “spirit” or “medicine” from “ritual.” If frankincense cleared a room and calmed a cough, great. If myrrh soothed grief and closed a wound, even better. The lines were blurred because they needed to be — life was rarely separate from death, and healing couldn’t afford to be one-dimensional.

Which makes you wonder: If they could do that without refrigeration, stainless steel, or synthetics… what exactly have we forgotten?

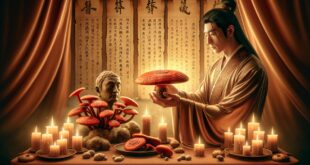

Spiritual and therapeutic roles in religious rituals

Step into any ancient sanctuary—whether a hilltop altar in Canaan, a Persian fire temple, or the heart of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem—and you’d likely find the air thick with fragrant smoke. That wasn’t for mood lighting. Frankincense and myrrh were the atmosphere, the offering, and often, the medicine. Their roles in spiritual rituals weren’t fringe customs—they were central, daily acts of reverence and restoration.

Step into any ancient sanctuary—whether a hilltop altar in Canaan, a Persian fire temple, or the heart of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem—and you’d likely find the air thick with fragrant smoke. That wasn’t for mood lighting. Frankincense and myrrh were the atmosphere, the offering, and often, the medicine. Their roles in spiritual rituals weren’t fringe customs—they were central, daily acts of reverence and restoration.

“He who sings prays twice,” said Augustine. But in temple traditions reaching back far beyond him, it was the smoke that sang—wordless, rising, a message without text.

Here’s the thing: ritual wasn’t separate from daily life back then. People didn’t light incense just to “get in the mood” or check off a spiritual to-do list. The resins carried actual weight. When frankincense was burned, it wasn’t just about scent—it purified spaces, signaled resets in energy, and shifted the nervous system into deeper stillness. In modern terms, you’d call it supporting the parasympathetic state. Back then, it was simply called sacred practice.

According to research cited by the NCBI, the smoke of frankincense includes incense acetate derivatives shown to act on ion channels in the brain—offering a plausible scientific basis for the resin’s calming effects.

Picture a temple priest near the Ark of the Covenant, his robes heavy with sacred oil, lighting the incense at dawn. The frankincense doesn’t just smell nice—it’s signaling a shift in consciousness, veiling the visible in the invisible. Much of biblical medicine, when you strip the marketing off, is a practice of tending energy through matter. These resins merged the seen and the unseen without drama.

Let me explain with a common example: in early Christianity, myrrh was used in chrism—the consecrated oil applied during baptism, confirmation, and anointing of the sick. Its bitter profile wasn’t accidental. Myrrh grounds, centers, and reminds the body what’s real without numbing it. When grief, birth, death, or initiation came, myrrh helped anchor the transition. It worked on both literal wounds and metaphorical ones.

You ever sat with someone in mourning? Not tried to fix it—just held space? That’s what burning myrrh did in sacred spaces. It held presence without needing to fix or explain. And that’s its quiet genius—myrrh doesn’t sedate pain, it dignifies it.

How these resins held fast across belief systems

It wasn’t just the Hebrews or early Christians that turned to these resins. Zoroastrian priests burned frankincense during Yasna ceremonies as part of the oldest known continuous fire-worship tradition. Their goal was communal purification, no less physical than spiritual. The thick plumes weren’t decoration—they were part of the process, like sterilizing a room before surgery… except here, the “surgery” was attunement of the soul.

You’ll even find mentions in Vedic rituals, where frankincense—called “dhoop”—was burned during homa (fire ceremonies) to invoke healing energy and protect sacred vows. Across these cultures, the theme repeats: smoke lifts prayers, purifies air, and calms hearts. The ritual wasn’t for ritual’s sake—it was maintenance. Tending the unseen aspects of health that modern medicine too often neglects.

As the Book of Exodus puts it, God instructed Moses to create a holy incense “blended as by the perfumer,” using frankincense and other spices “in equal parts.” That wasn’t random — it was aromachemistry guided by spirit.

The therapeutic side of a sacred flame

Let’s talk real-world effects for a second. Burn a high-quality chunk of Boswellia sacra (frankincense resin) in your home and pay attention—not just to the scent, but how your breathing shifts. There’s a lightness that settles in. Not numbing like a sedative, but clarifying. That’s not mystical fluff—it’s chemical. Studies, including this publication in the Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, show that frankincense oil affects heart rate and breathing in measurable ways, reducing signs of physiological stress.

Now layer in intention. Ritual amplifies effect. Light the resin with a simple prayer—not a wishlist or script, just presence. That moment becomes therapeutic not because of belief alone but because time slows down—it’s framed. And the resin carries that frame in its molecular structure.

This is why calling these “essential oils” is sort of missing the point. Their value wasn’t essential because of chemistry alone. It was essential because it touched something people knew they couldn’t explain with words—only with silence, song, and smoke.

Even the messiness had meaning

Here’s something practical yet philosophical: the act of burning resin isn’t clean. It involves ashes, heat, a risk of singed fingers, maybe the need to relight a smoldering chunk. That process—the patience, the presence, the trial and error—was part of the spiritual effect. Today’s prepackaged incense sticks and aerosol air fresheners mimic the outcome without honoring the process.

But ask anyone who’s ever sat in stillness beside a Frankincense burner in a candlelit room—the whole thing is the medicine.

So when we call frankincense and myrrh part of “biblical medicine,” it’s not just nodding to ancient prescriptions. It’s acknowledging that spiritual care—grief tending, blessing, protection, setting space—is every bit as critical as treating symptoms. That dual function was never separated in the first place.

And maybe that’s the call now: not to mimic ancient rituals for aesthetics, but to remember why they were created in the first place.

Because there’s something honest about tending a small flame while the room shifts from chaos into quiet. Something useful, healing, and real. Even without words.

DS Haven In Light Of Things

DS Haven In Light Of Things